There are two sources of information for Queen

Alexandra’s purchases from Fabergé from which it is possible

to build up a picture of her buying habits. These are her

own accounts, a proportion of which survive in the Royal

Archives, and the sales ledgers from the London branch which

are held in the Fabergé Archive in Geneva. Queen Alexandra’s own accounts reveal that between 1902 and 1914 a total

of £3,197 was spent with Fabergé. Of that total £2,614 was

paid from the Queen’s presents account, indicating that many

of the objects were given away rather than kept by her.10

The remaining £583, paid from a ‘miscellaneous’ account,

must relate to objects she kept.

The London ledgers are an invaluable source of information as they indicate the types of objects purchased by

Queen Alexandra as presents. It is reasonable to assume that

any of these objects which do not now form part of the collection were paid for from the presents account. The ledgers

run from October 1907 to January 1917. There are no entries

in the ledgers between October 1906 and October 1907, probably due to reorganisation following the end of Fabergé’s

business arrangement with Allan Bowe. Fabergé was obliged

to close the London branch in 1915 to comply with the imperial order that all capital abroad should be returned to Russia

in order to finance its war effort, but H.C. Bainbridge carried

on the business privately for another two years.

At first there were no import taxes on objects brought

into England by Fabergé and the laws on hallmarking gold

allowed for wide interpretation. Fabergé refused to have his

objects hallmarked in England for technical reasons. As a result

the Goldsmiths’ Company brought a court case against him

the Goldsmiths’ Company brought a court case against him

in 1910 which took more than a year to settle and which Fabergé

lost. Birbaum describes how, following the case, the process

of sending objects to be sold in the London branch became

complex. Each silver or gold object had to be sent to London

to be hallmarked and then returned to Russia to be finished before being sent back to London to be sold. The reason

for the double journey was that when enamelled objects were

hallmarked, some separation occurred between the enamel

and the metal. It was therefore necessary to carry out finishing back in Russia. According to Birbaum, it was deemed

that this process would lead to losses for the firm; the closure

of the London branch was therefore hastened, rather than initiated, by the First World War.11

Queen Alexandra made the majority of her purchases

at the London branch in the Easter and Christmas seasons,

which underlines the fact that many were intended to be given

away. She purchased most frequently between 1906 and 1911,

the largest number of objects (thirty-three) being bought in

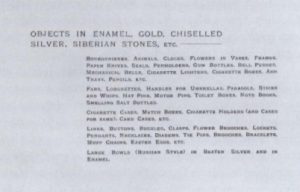

1909. Her acquisitions ranged from animals and cigarette

cases to miniature eggs and frames. She also bought a number of pieces of jewellery, very few of which remain in the

collection. While there is no record of any direct commission,

the special relationship that the Queen had with Bainbridge

must have resulted in some objects being specially designed

for her. One such example is the frog cigar lighter (cat. 82)

which she purchased for King Edward VII in 1906. It is so

much in keeping with his taste that she is likely to have ordered

it specially for him.

The most notable exhibition of Fabergé during the

early years of the twentieth century was held in St Petersburg

in 1902 and included several of the Imperial Easter Eggs,

among other treasures. The only exhibition held during the

same period in England, in fact the first ever to be staged there,

was organised by Lady Paget, wife of General Sir Arthur Paget.

It was held in June 1904 at the Albeit Hall and took the form of a charity bazaar in aid of the Royal Victoria Hospital for

Children. Queen Alexandra gladly lent her support, apparently purchasing a jade scent bottle and an enamel and diamond

cigarette holder, both made by Fabergé.