THE NAME OF FABERGE is synonymous with luxury objects

and jewellery made to exacting standards from the

finest materials. It should be noted that while his work

was eclectic by nature, drawing on a wide range of design

sources, it encapsulated the style of a whole period at the end

of the nineteenth century and beginning of the early twentieth

century. Supported by Faberge’s international reputation,

this style proved deeply influential on goldsmiths and jewellers

based in Russia and encouraged others abroad to imitate

his products. He counted not only the Russian imperial and

British royal families as his best clients, but most of the

royal houses of Europe, along with aristocrats and wealthy

businessmen around the world. The importance of the British

royal family among Faberge’s clients has already been outlined

and their contribution to his success is evident, but they did

not confine their patronage to him. Similarly, the Russian imperial

family bought from other jewellers and goldsmiths, with

the result that objects by other makers were given as official

presents and in some instances entered the Royal Collection

as gifts (e.g. cat. 357). The works of art by other makers included

here provide a representative rather than a comprehensive

overview of both Russian and European competitors of Faberge

and give an insight into the acquisition of works in Faberge’s

style by members of the royal family.1

Although Gustav Faberge had begun to supply the

Imperial Cabinet in 1866, it was not until his son Carl received

the official tide of Supplier to the Court of His Imperial Majesty

Tsar Alexander III in 1885 that the firm became a major

supplier. Ten years later the death of Alexander III, followed

by the wedding and coronation of his heir, Nicholas n,

brought an overwhelming number of commissions to the jewellers

and goldsmiths of St Petersburg and Moscow. While

Faberge was awarded many of the most important commissions

and was eventually to become the most prolific royal

jeweller, there were several other firms that were already wellestablished

suppliers to the court.

The firm of Bolin was established by Carl Edvard

Bolin in St Petersburg in the 1830s and was the main supplier

of presentation orders and decorations to the court. From

1839 Bolin was appointed official jeweller to the imperial court

and the firm became the foremost jewellery business in

Russia. It was not until the 1890s that Faberge emerged as

Bolin’s main competitor. In spite of the originality of its

jewellery, much of which was in the art nouveau style, Bolin’s

firm took inspiration from Faberge for certain products. They

made fine gold and jewelled cigarette cases, but in general

their work lacked the refined elegance and sophistication

of Faberge’s designs. Given the longevity of Bolin’s firm

and the close links between the Russian and English royal families,

it is surprising to find that there are now no works by

Bolin in the Royal Collection. Queen Alexandra’s accounts

reveal that she made only one purchase from the firm, in January

1904, of a brooch costing £41;2 the brooch has not been

identified. Between 1912 and 1932 Queen Mary acquired the

only recorded Bolin piece to enter the Royal Collection, a

green enamel cigarette case very reminiscent of Faberge’s style.

Sadly, this object cannot now be traced.3

Another major competitor of Faberge, but not represented

in the Royal Collection, was the firm of Tillander.

Established by Alexander Tillander in St Petersburg in 1860,

from the 1890s the firm supplied the court with presentation

items such as brooches, cufflinks and tie-pins incorporating

the imperial emblems. The firm also made jewellery, miniature

Easter eggs, cigarette cases and picture frames – often in

the style of Faberge – and had a loyal following among the

nobility and industrial magnates of St Petersburg. In April

1911 the firm moved to 26 Nevsky Prospect, taking over

the premises formerly occupied by the court jeweller Hahn.

Tillander established a long-lasting and lucrative collaboration

with the Parisian jeweller Boucheron (also a competitor

of Faberge) after the assassination of the latter’s Moscow representatives

in 1911.

Karl August Hahn established his firm in St Petersburg

in 1873. In 1896 Hahn was commissioned by Tsar Nicholas

II to produce a diadem to be worn by Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna

at her coronation. Hahn was subsequently appointed

supplier to the court and provided a range of objects including

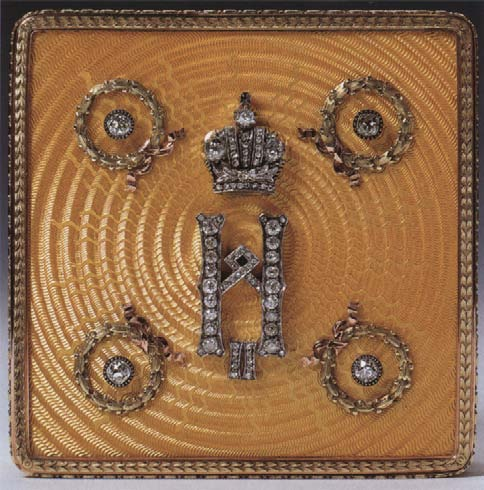

box by

Faberge, 189&-

1908 (cat 145)

and (below) an

imperial presentation

box by

Faberge’s

competitor Hahn,

c. 1900 (cat. 354).

presentation boxes, cigarette cases and frames. Presentation

boxes were the traditional gift of the tsar to foreign high-ranking

dignitaries and a prestigious award to Russian subjects

of high merit. In general, Hahn’s presentation boxes, while

suitably opulent, are less up-to-date in style and the enamelling

incorporates a more limited colour palette than that

used by Faberge. A comparison of a presentation box by Hahn

(cat. 354) and one by Faberge (cat. 145) reveals the differences

between the two makers. The Hahn box is a litde old-fashioned

in shape and the guilloche enamelling, while finely executed,

shows a limited range of patterns. The Faberge box by

contrast is engraved with an exciting variety of patterns which

are almost three-dimensional in quality when seen through

the translucent yellow enamel. From 1892 Hahn employed as

a head workmaster the independent goldsmith and jeweller

Carl Blank, who became a partner in the business from 1911.

He produced work of a very high standard, most evident in

the objects that bear his mark in conjunction with that of Hahn.

The presentation cigarette case (cat. 355) is a fine example of

guilloche enamelling by Blank and compares well with Faberge’s

work, except for the large hinge and clumsy closing mechanism.

In spite of the quality of Blank’s enamel, it is generally

accepted that Faberge was producing the finest enamelling of

the period; no other maker approached, for example, the enormous

range of colours he produced. Although competitors,

the two firms sometimes collaborated. Hahn was responsible

for remounting Faberge’s presentation boxes, which were

occasionally returned to the Imperial Cabinet by their recipients

for a variety of reasons. The boxes would then be recycled

and presented to another recipient. This often involved removing

the portrait miniatures applied to them and replacing these

with the diamond-set cypher of the Tsar. After the death of

Dimitri Hahn (Karl August’s son), the business premises were

taken over by Tillander and Carl Blank returned to working

independently. According to Valentin Skurlov, Blank continued

to fulfil commissions for the Imperial Cabinet for orders

and decorations.4

The firm of Ovchinnikov was founded by Pavel

Ovchinnikov in Moscow in 1853. The business expanded

quickly to become a major supplier of silver and enamel objects

in the Pan-Slavic or Old Russian style. In 1873 Ovchinnikov

opened a branch of his business in St Petersburg, run

by his son Michael. Ovchinnikov’s success rested on his

cloisonne enamelling, which was widely recognised as being

of excellent quality. The firm became known in the rest of

Europe when its work was exhibited at the Exposition Universelle

in Paris in 1900. A set of salts in the Royal Collection

(cat. 364) demonstrates Ovchinnikov’s use of cloisonne enamelling

in jewel-like colours and is a good example of the firm’s

traditional Russian-style objects. Faberge was also producing

pieces in the Old Russian style from his Moscow workshop

from the 1890s onwards. These were mainly enamelled by

Feodor Riickert, who produced the highest-quality cloisonne

enamelling for the firm (see cat. 325). The date of acquisition

of the set of salts is unknown but they are likely to have

been acquired by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

Queen Alexandra’s accounts reveal that she was a customer

of Ovchinnikov; she made purchases from the firm of jewellery

and ‘Russian objets d’art* between 1905 and 1911

amounting to £1,000, paid for from her miscellaneous account,

but none of these objects appears to survive in the Collection

today.5 King George V was also a customer of the firm, as

an invoice in the Royal Archives reveals. It appears that the

King purchased two cigarette cases, a squirrel and a rabbit

both in purpurine, two aquamarines and three amethysts in

July 1911. The invoice was issued from Paris, indicating

that Ovchinnikov made further selling trips to the Continent,

but the items were purchased in England.6

There are two works in the Royal Collection by the

St Petersburg goldsmith Ivan Britsin. Britsin’s workshop specialised

in the production of guilloche enamel objects in the

style of Faberge. The frame and seal included in this exhibition

(cat. 348 and 366) are enamelled in Britsin’s characteristically

limited palette of colours in which white featured heavily.

According to Von Habsburg, Britsin occasionally supplied

Faberge, whose mark appears in combination with his own on

a number of pieces.7 The frame and seal in the Royal Collection

were acquired at an unknown date by Queen Elizabeth.