The King’s knowledge and clear enjoyment of Fabergé’s

work encouraged many of his friends and contemporaries

to become clients of Fabergé. These included some of the best

customers of the London branch, such as Stanislas PoklewskiKoziell, a councillor at the Russian Embassy in London, Leopold

de Rothschild, Sir Ernest Cassel, Lord Revelstoke, the Duke

of Norfolk and the Marquis de Soveral. The London ledgers

are full of the names of royalty and aristocrats from every corner of Europe and the Indian sub-continent. While many

of Queen Alexandra’s Fabergé objects were intended to

charm and delight and were arranged in her cabinets at her

whim, the more practical items acquired by the King were

regularly used. They sometimes required repair, and there

are several entries in the London ledgers for re-enamelling

cigarette cases owned by King Edward VII and later by

King George Y

Princess Victoria (1868-1935), the second daughter of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, inherited

her parents’ interest in Fabergé. She was a good customer

of the London branch and purchased many pieces both for

her own collection and as gifts. She often accompanied Queen

Alexandra on visits to the London branch, where they would

enjoy examining pieces newly arrived from Russia in what was

in effect their private showroom. Her own small collection

was principally of animals and flowers, but she purchased a

range of objects including several pieces of jewellery, such

as tie-pins, pendants and brooches. She also bought cigarette

cases and an unusual frame with miniature views of St Petersburg (cat. 229). Princess Victoria inherited several pieces from

her mother, such as parasol handles, flowers and animals.

As she did not marry, these were bequeathed to King George

V after her death.

Possibly an even greater admirer of Fabergé than his

sister, King George V acquired many pieces both as Prince of

Wales and later as King. He was particularly enamoured of the

animal sculptures and bought many of those originally commissioned by his father in 1907. Several of the portrait sculptures

from Sandringham were of dogs owned by him and kept at

the kennels there, such as the Clumber spaniel Sandringham Lucy (cat. 20). He describes in his diary numerous visits

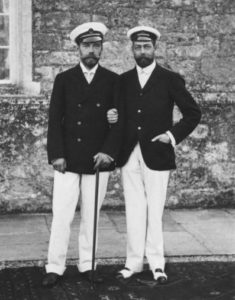

George V), at barton Manor, Isle of Wight, August 1909.

to Fabergé’s London branch. On 3 May 1903 he reports some

early purchases, either at the branch or on a visit by Fabergé

to Marlborough House: ‘he [Fabergé] has just come over from

Russia, we bought about 43 of his lovely things.’16

As Duke

of York, he had visited Fabergé’s St Petersburg headquarters with his father in 1894 while attending the funeral of Tsar

Alexander lit and the marriage of Tsar Nicholas II and Princess Alix of Hesse. During this time he also visited the Baron Stieglitz

School in St Petersburg where many of Fabergé’s designers

and craftsmen were trained. King George V describes with

great affection the occasions on which he met his

Russian cousin, notably at Cowes in August 1909 when the

imperial family arrived aboard their yachts the Standart and

the Pole Star. He recalls that he had not seen the Tsar and

Tsarina for twelve years. Nine years later, in July 1918, after

the brutal murder of the Tsar and his family, the King wrote

in his diary, ‘I was devoted to Nicky, who was the kindest of

men, a thorough gentleman, loved his Country & his people.’17

Just as happened among his parents’ generation, gifts were

exchanged on occasions such as the meeting at Cowes. There

are letters from the King to the Tsar, held in the Russian State

Archive which record the King’s thanks for gifts at Christmas

in 1906,1908-10 and 1912. The gifts described include a stick

handle, some vases, a match box, a cigarette case and a

bust of the Tsar. At least some of these would have been

supplied by Fabergé.18

In addition to the animal sculptures which King

George V particularly liked, he also added to the collection

desk accessories, cigarette cases and frames. He used such

items as the desk clock (cat. 276) and the pen rest (cat.

285) at Buckingham Palace.19

His most notable acquisitions were, however, made long after the London branch had closed. In the 1930s, together with Queen Mary, he bought

the three Imperial Easter Eggs now in the Royal Collection.

They both continued buying works by Faberge from a number of different sources after 1917, including the dealer Wartski

and Goode’s Cameo Corner. The firm of Wartski had been

established in London from 1911 by Emanuel Snowman, one

of the first Western dealers to bring works by Faberge out

of Russia after the Revolution. Queen Mary acquired numerous pieces from the firm, notably the Easter egg made for the

Kelch family (cat. 4).

Queen Mary acquired a large number of pieces

for the collection, mainly in the form of cigarette cases and

snuff boxes given to King George V who owned many such

objects. She also received many gifts from the imperial family,

such as the nephrite box given to her in 1912 by the Dowager

Tsarina Marie Feodorovna (cat. 150), and from her friends,

many of whom were noted Faberge collectors. Two examples are the bonbonniere with views of Balmoral Castle and

Windsor Castle which was given to her for her birthday in 1934

by Sir Philip Sassoon and the imperial presentation box given

by the Maharaja of Bikanir for her birthday in 1937 (cat.

177 and 142).

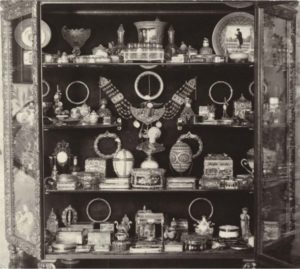

Faberge collection in a

display cabinet at

Buckingham Palace, c.1950.

Pieces purchased by Queen Mary from the London

branch included miniature eggs, animals, bell pushes and flowers, but it seems the majority were intended as gifts, as

many of them no longer survive in the collection. As a renowned

collector of objets d’art of all kinds, Queen Mary kept fastidious records of all the pieces she acquired for the Royal

Collection, which were listed by year of acquisition and by

type of object, and for each of her acquisitions she made a

record of the provenance of the piece as given to her.20

Her

taste ranged from eighteenth-century gold snuffboxes to lacquer and jade, but she had a particular fondness for Faberge.

In many respects she may be regarded as the first serious collector of his work in the British royal family. It was not without

reason that Bainbridge described Queen Mary in 1949 as ‘the

greatest surviving connoisseur of Faberge’s craftsmanship’,21

and among King George V’s papers in the Royal Archives is a

list of all the Faberge workmasters annotated in her hand, noting how useful the document was.22

Queen Mary was instrumental in influencing a whole

generation of collectors who sought to acquire pieces with

imperial provenance. Her own most notable acquisitions were

the three Imperial Easter Eggs purchased with King George V

in the 1930s, but in addition to her collecting, she stimulated interest in the subject of Faberge by attending sale views

and exhibitions and paying regular visits to West End dealers.

She twice visited the Russian exhibition held in Belgrave Square in 1935, on 30 May and again on 14 June, when she recorded:

Vent to the Russian Exn. again at 7 (when the public had left).

Met by Mr C. Faberge’s son & Mr Bainbridge. Looked at the

china, silver, & the Faberge things, most interesting’.23

Sir

Owen Morshead, the Librarian at Windsor Castle, went to

the same exhibition and wrote to Queen Mary on 4 June,

encouraging her to attend the exhibition and to meet, through

Lord Herbert, Faberge’s son.24

Connoisseur magazine gave

a lively review of the exhibition, which had been opened by

the Duchess of Kent and to which Queen Mary had made

several loans.25

On 31 January 1949 Queen Mary visited

Sotheby’s to view ‘some Faberge things and very pretty trinkets’26

which had belonged to Sir Bernard Eckstein, the noted

collector and Faberge enthusiast. One of the objects sold at

the series of six Eckstein Collection sales was the Imperial

Easter Egg known as the Winter Egg, which sold in New %rk

in 2002 for $9.5 million. In 1949 it had realised £1,700. Another

of the pieces included in the same sale was the convolvulus

plant, now in the Royal Collection (cat. 123), which was given

to Queen Mary by the royal family on her birthday in May

1949.27